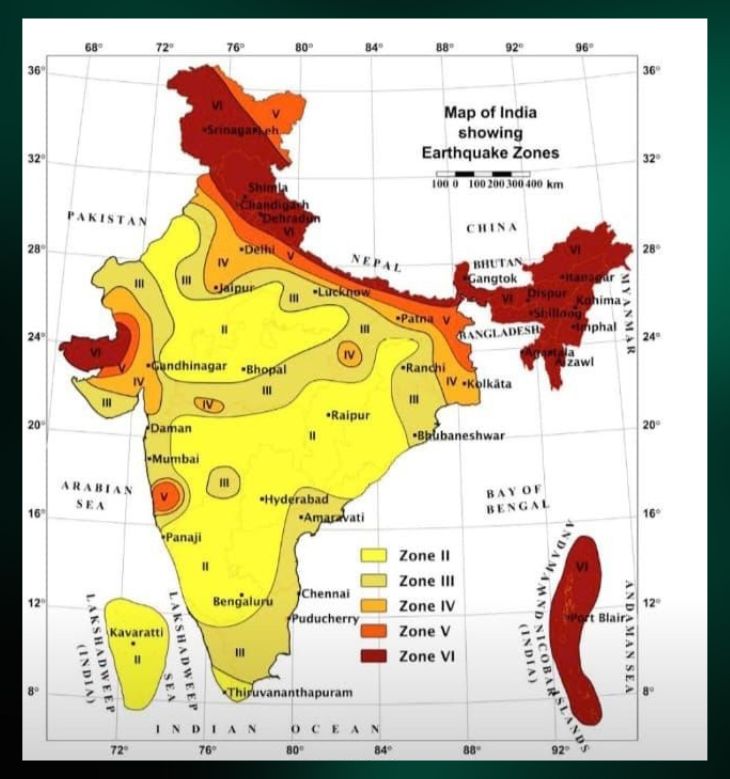

India’s continuous tectonic engagement at the northern frontier, where the Indian Plate relentlessly pushes beneath the Eurasian Plate, makes the subcontinent one of the world’s most seismically vulnerable regions. Historically, India’s seismic zoning map, which forms the bedrock of building codes and disaster preparedness, had been classified into four categories, with Zone V being the highest risk. However, recent geological and seismological evidence, particularly the accumulated strain along the Himalayan arc, has necessitated a radical overhaul.

The introduction of Zone VI, the most severe seismic classification, under the revised Earthquake Design Code (BIS 2025) signifies a major recalibration of the nation’s hazard assessment. This change acknowledges a heightened risk profile and mandates a fundamental shift toward rigorous safety standards and comprehensive urban resilience across over 61% of India’s landmass, where the majority of the population resides. The recognition of a New Earthquake Zone in India is not a cause for panic, but a critical call for national action.

The Evolving Seismic Landscape: India’s New Hazard Map

The updated seismic zonation map is a product of modern scientific rigour, moving beyond reliance on just historical records to model the true seismic potential of active faults.

1. Introduction of Zone VI: A Major Reclassification

The creation of Zone VI represents the most significant update to India’s seismic map in decades. This new category is designated for areas where the expected intensity of ground shaking is highest and most destructive. The entire Himalayan belt, which was previously inconsistently demarcated across Zone IV and Zone V, has now been placed under this unified, highest-risk category.

This reclassification is driven by the consensus among seismologists regarding the immense, accumulated tectonic stress along the Himalayan Frontal Thrust (HFT). The long-locked segments of the Central Himalayas, especially the areas bordering Uttarakhand and western Nepal, have not experienced a major earthquake (Magnitude M8.0+) for nearly two centuries. This seismic gap indicates a colossal build-up of energy, making these regions capable of generating a “Great Earthquake.” By establishing Zone VI, the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) has provided a clear, non-negotiable mandate for the most stringent seismic design for structures throughout this entire arc, finally reflecting the consistent, extreme tectonic threat across the region. The New Earthquake Zone in India is a geographic reality, not an administrative choice.

2. Shift from Historical Data to Probabilistic Modelling

The previous seismic map was based primarily on a deterministic approach, using the locations and magnitudes of past earthquakes to define zones. This model often underestimated the future risk posed by currently quiet, but critically strained, fault segments.

The new map, integral to the BIS 2025 code, adopts the internationally recognised Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Assessment (PSHA) methodology.

PSHA integrates complex scientific data, including active fault geometry, crustal strain rates (often measured by GPS), and regional ground-shaking attenuation characteristics.

The PSHA model estimates the probability of experiencing a certain level of ground motion (often Peak Ground Acceleration or PGA) at a specific site within a given timeframe (typically a 10% chance of being exceeded in 50 years).

Furthermore, the new code implements a key rule change: any city or town located on the boundary between two hazard zones is automatically assigned to the higher-risk zone. This enhancement ensures that geological reality and potential consequences take precedence over administrative lines, fundamentally improving earthquake safety.

Detailed Breakdown of India’s Five Seismic Zones

The updated zonation divides the country into five distinct categories, defining the minimum levels of earthquake-resistant design required by the new codes. This five-zone classification provides engineers and urban planners with the fundamental parameter—the Zone Factor—to calculate the seismic forces a structure must be designed to withstand.

| Seismic Zone | Risk Level | Description of Risk | Maximum Expected Intensity (MSK Scale) | Design Acceleration Factor (Z) |

| Zone VI (New) | Extreme / Ultra High Risk | Regions with the highest expected ground acceleration, primarily encompassing the fully strained Himalayan arc. | X (Extreme Damage) | Highest Factor (Significantly increased from old Zone V) |

| Zone V | Very High Damage Risk | Regions with historic seismic activity capable of causing destructive-level damage. | IX (Destructive) | 0.36g |

| Zone IV | High Damage Risk | Regions expected to experience significant damage, requiring advanced earthquake-resistant construction. | VIII (Very Strong) | 0.24g |

| Zone III | Moderate Damage Risk | Regions where moderate seismic events are expected, demanding intermediate design measures. | VII (Strong) | 0.16g |

| Zone II | Low Damage Risk | Regions with the lowest historical and predicted seismicity, requiring only minimum standard design. | VI or Less (Light) | 0.10g |

The Zone Factor (Z) directly influences the seismic coefficient (Aₕ) used in structural design calculations: Ah = (Z / 2) × (I / R) × (Sa / g). The introduction of the New Earthquake Zone in India (Zone VI) mandates a significantly larger (Z) factor than the previous Zone V, resulting in higher required strength and ductility for construction.

State-wise Breakdown: Which State Falls in Which Zone?

The revised zoning has a profound impact on several states, particularly those along the Himalayan and Northeastern boundaries. The shift to Zone VI represents a unified risk assessment for the entire mountain range.

Zone VI: The Entire Himalayan Arc & Northeast

This zone is defined by the high-velocity collision boundary and includes regions with the greatest potential for great earthquakes. The entire width of the Himalayan mountain system and the historically active Northeast are covered:

Entire States/UTs: Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Tripura, Nagaland, Meghalaya, and the major part of Assam.

Other Key Areas: Large portions of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh (eastern sections), and the seismic gap region of North Bihar adjoining Nepal.

Zone V: Regions of Gujarat, Parts of J&K, North Bihar & A&N Islands

This pre-existing highest-risk zone retains crucial areas of high vulnerability outside the new Zone VI.

Kutch region of Gujarat: Site of the devastating 2001 Bhuj earthquake (an intraplate quake).

Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Due to their location on the active plate boundary of the Indo-Australian and Eurasian plates.

Remaining high-risk pockets in North Bihar and specific areas of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh.

Zone IV: NCR Delhi, Remaining Himalayan States & Indo-Gangetic Plains

This high-damage-risk zone includes major metropolitan and populous areas that face significant shaking risk, often from great earthquakes originating in the Himalayas.

National Capital Region (NCR) Delhi and surrounding regions of Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh.

Major parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plains (Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal).

Coastal metropolitan cities like Mumbai and Kolkata (where soil amplification can increase shaking intensity).

Zone III: Peninsular Plateaus, Parts of Coastal and Central India

This moderate-risk zone is crucial because it includes regions previously considered relatively stable but where damaging intraplate earthquakes (like Killari, 1993) have occurred.

Major portions of Peninsular India (large parts of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh).

Coastal areas of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Most of Central India (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha).

Zone II: The Least Vulnerable Regions of the Deccan Plateau

This zone represents the areas with the lowest risk of seismic hazard, mostly comprising the stable core of the Deccan Plateau. Even here, however, minimum earthquake-resistant detailing is mandatory for all construction.

The New Earthquake Design Code (BIS 2025)

The seismic map is implemented through the Revised Earthquake Design Code (IS 1893:2025). This code transforms the theoretical risk defined by the new zones into practical Seismic Resilience requirements for the construction industry.

1. Mandatory Seismic Design Standards

The BIS 2025 code introduces stricter technical mandates aimed at ensuring buildings are designed to withstand the intensified shaking expected from a New Earthquake Zone in India:

Liquefaction Assessment: Mandatory site-specific geotechnical investigations are required, particularly in alluvial and coastal areas, to assess the risk of soil liquefaction, where saturated soil temporarily loses strength during an earthquake.

Near-Fault Provisions: Structures located near known active faults must now be designed for pulse-like ground motions—severe, high-velocity shaking that is extremely damaging to buildings—a provision largely absent in previous codes.

Safety of Non-Structural Elements: For the first time, the code mandates strict safety measures for non-structural components (parapets, facades, overhead tanks, false ceilings, HVAC units, and lifts). These elements are often the cause of casualties in moderate quakes and must be securely anchored if their weight exceeds 1% of the total building load, ensuring a more comprehensive approach to life safety.

2. Retrofitting for Critical Infrastructure

The code also underscores the urgent need to address the vulnerability of existing infrastructure, especially in the newly upgraded Zone VI areas. A national program for the seismic audit and retrofitting of crucial lifeline facilities is mandated:

Lifeline Continuity: Upgrading Hospitals, Schools, Bridges, Dams, and Communication Centres to ensure they remain functional immediately after a major seismic event.

Urban Renewal: Large-scale public awareness and capacity-building programs for local authorities are required to accelerate the structural strengthening of older residential buildings that predate modern seismic codes.

Implications for Urban Planning and Safety

The implications of the New Earthquake Zone in India are wide-ranging, necessitating a fundamental change in the economics and governance of urban development in vulnerable areas.

1. Impact on Real Estate and Construction Costs

The shift to Zone VI immediately impacts the cost of construction. Higher seismic design factors mean mandatory use of:

Increased Structural Components: More steel reinforcement, higher-grade concrete, and deeper, more complex foundations.

Compliance Costs: Mandatory geotechnical studies and adherence to new non-structural anchoring rules add to the initial investment.

While this may lead to a 10-15% increase in initial construction costs in the highest-risk areas, this investment ensures long-term durability, safety, and resilience, ultimately protecting property value and reducing the potentially catastrophic financial losses associated with structural collapse.

2. Public Awareness and Disaster Preparedness

The new map provides the necessary scientific clarity for targeted disaster planning.

Risk-Informed Planning: Municipalities must incorporate the new zoning into city master plans, enforcing land-use restrictions in liquefaction-prone and active fault areas. The New Earthquake Zone in India must be the basis for all future expansion.

Community Education: State Disaster Management Authorities must leverage the clear, escalated risk profile to drive focused training, mock drills, and public education campaigns, ensuring that citizens in Zone VI understand the severity of the hazard and the necessity of complying with stringent building standards. The goal is to embed a culture of Seismic Resilience at the community level.

Conclusion: A Call for Unified Resilience

The revision of India’s seismic map, headlined by the creation of Zone VI, is a bold, science-backed step toward New Earthquake Zone in India preparedness. By leveraging PSHA methodology, the BIS 2025 code has issued a clear directive: the nation must build safer, stronger, and more resilient infrastructure, especially along the highly vulnerable Himalayan arc. This transition requires unified effort from policymakers, engineers, the construction industry, and the public. By investing in strict adherence to the new codes, India safeguards its urban assets and, more importantly, protects the lives of its citizens against the inescapable reality of future earthquakes.